Countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia achieved independence in 1991 after the Soviet Union dissolved. Following this, they began a transition from Soviet command economies to market economies during the 1990s. The success of this transition varies significantly from country to country. For example, Georgia has made notable progress in establishing a market economy, particularly through reforms in the early 2000s under President Mikheil Saakashvili, which focused on deregulation, privatisation, and anti-corruption measures. Armenia has also made progress, though at a slower pace compared to Georgia. In contrast, Turkmenistan remains highly centralised and state-controlled, with little progress in implementing market reforms. Uzbekistan has also been slower to transition compared to some of its neighbours. Under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, however, the country is taking steps to liberalise the economy and improve the business environment.

Most CCA countries are still closely associated with Russia through the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which is a free association between former Soviet countries that promotes cooperation. The CIS facilitates trade among member states by reducing trade barriers and promoting a free trade area. Moreover, it facilitates labour migration in the region. Many workers from CIS countries, particularly from Central Asia, migrate to Russia and Kazakhstan to seek employment.

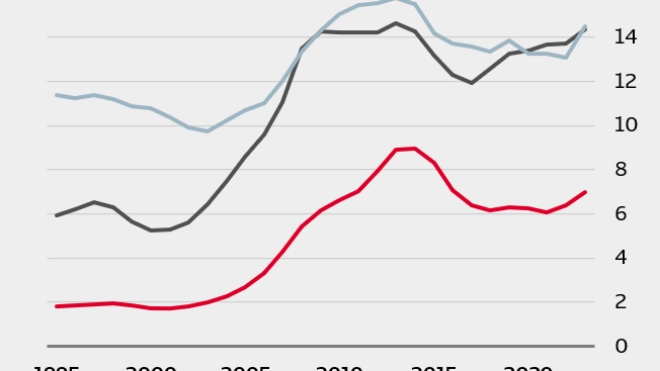

The degree of economic success varies considerably across the CCA region. The average income level in CCA rose from just under 2% of the United States level in 1995, to 7% of the US-level in 2023. Despite substantial income growth, none of the countries in Central Asia have been promoted from middle-income to high-income since independence from the Soviet Union. In 2023, the threshold for being classified as a high-income country was USD 14,005, according to the World Bank. The average income in the CCA region that year was USD 5,624, placing it at the lower end of the upper-middle-income bracket.

The income level relative to the US has even dropped since 2014, when measured at market exchange rates (figure 1). The same decline is visible when income levels would be measured relative to Advanced Europe. We use the GNI per capita measure (in USD, converted from local currency using the Atlas method ), which is used to set income thresholds for the World Bank’s country classification.

Since 1995, the CCA region has managed to slightly narrow its income gap with the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (excluding the Gulf states). Since 2015, however, the gap has widened again, as several countries in the MENA region, such as Djibouti, Israel and Malta enjoyed relatively high income growth. The income gap between the CCA region and countries in Central and Eastern European has grown bigger since 1995, as many of the countries in this part of Europe have joined the EU or are closely aligned with it, benefitting from increased reform pressure and greater trade opportunities.

Kazakhstan is by a substantial margin the richest country in the CCA region. In 2023, it had an average income level of roughly USD 10,700. Kazakhstan has the largest proven oil reserves in the Caspian Sea region and is one of the top oil producers globally. The energy sector is a major driver of its economy, significantly contributing to its GDP and export revenues.

Then there is a group of countries with income levels varying between USD 6,600 and USD 8,300. This group consists of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Turkmenistan. Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan are the more fossil-fuel oriented economies, while Georgia and Armenia are more diversified. Turkmenistan possesses the world’s seventh-largest natural gas reserves and is a significant player in the global gas market. The natural gas sector is crucial for Turkmenistan’s economy, providing substantial export revenues. Azerbaijan relies heavily on both oil and gas, which account for 50% and 40% of its export revenues, respectively.

Armenia and Georgia, on the other hand, are less reliant on fossil fuels and have more diversified economies, with a larger share of services compared to other countries in the region. Armenia has a growing IT sector and is known for its production of machinery, textiles, and food products. Georgia's economy is service-oriented, with tourism, finance, and real estate being major sectors.

The relatively poorer countries in the CCA region are Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The poorest of this group is Tajikistan with an average income level of USD 1,400, followed by Kyrgyzstan (USD 1,800) and Uzbekistan (USD 2,700). Uzbekistan’s export structure is heavily weighted towards natural resources, including gold, cotton and natural gas. Kyrgyzstan's economy depends on agriculture, mining, and remittances. Tajikistan’s economy is similarly dependent on agriculture, aluminium production, and remittances. Remittances from Tajiks working abroad, mainly in Russia, constitute 32% of GDP, making it the most remittance-dependent country in the world. Kyrgyzstan's remittances are nearly as significant, accounting for 31% of its GDP.

An overview of economic growth in the Caucasus & Central Asia

The growth performance of countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia has been mixed. In the early 1990s the region endured a recession. The goods produced by Soviet-era capital stocks held little appeal for domestic consumers or foreign importers. Moreover, following the liberalisation of prices and the reorientation of trade patterns, some of the old capital stocks became obsolete.

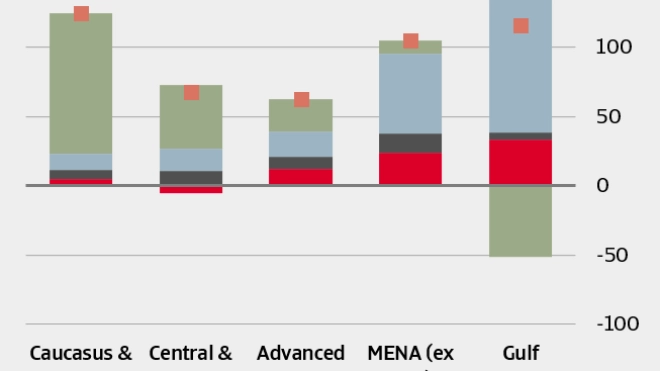

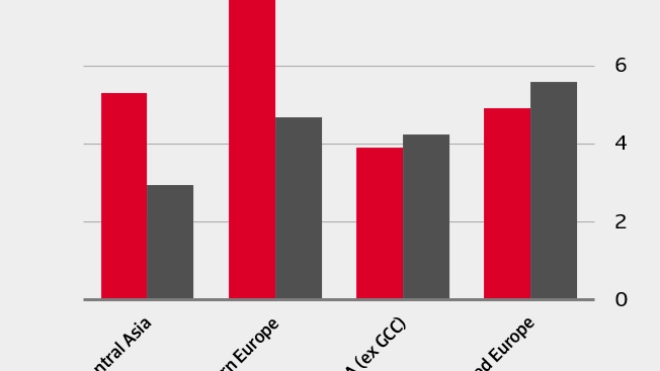

From the second half of the 1990s up to the Global Financial Crisis, there was a period of high GDP growth. However, compared with other emerging market regions, the drivers of this growth were fundamentally different (figure 2).

Physical capital growth was initially constrained by the depreciation of obsolete Soviet-era means of production. Countries in the CCA region had already comparatively old populations at the start of their transition process, so they did not benefit from significant growth in the labour force. Educational attainment was relatively high at the start of the transition process, comparable to levels seen in advanced countries. This provided the CCA countries with a clear advantage over many other emerging markets. However, this already high level of education limited the potential for further growth in human capital.

Instead, productivity delivered the most important growth contribution. This is seen in total factor productivity (TFP) growth, which refers to the efficiency with which factors of production – capital, labour and human capital – are combined to produce added value. Strong TFP growth in the CCA region reflects the transition from command economies to market economies, which supported a more efficient use of the factors of production.

At the time of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, the CCA region had caught up in terms of productivity compared to countries at a similar income level. In the years since the GFC, GDP growth has slowed, although it is still higher compared to Central and Eastern Europe and MENA (excluding Gulf Corporation Council). The lower GDP growth is largely due to a slowdown in productivity growth, as it becomes more difficult to sustain high productivity growth once the technology gap with advanced markets becomes smaller. The contribution of labour to economic growth remained limited, due to population ageing and emigration. Capital growth, however, has become a more important growth driver since the GFC.

Transitioning to high-income status: prospects for CCA Countries

Can countries in the CCA region make the step from middle-income to high-income status? Since 1990, only 34 economies have been promoted from the middle-income to the high-income group. Examples are Saudi Arabia, Latvia, Bulgaria and South Korea. Failure to transition to high-income status is known as the ‘middle-income trap’, which is a situation in which a middle-income country experiences systematic growth slowdowns as it is unable to take on the new economic structures needed to sustain high-income levels. Drawing on decades of development experience, a recent report from the World Bank outlines strategies for developing countries to avoid being stuck in the middle-income trap (see Box 1).

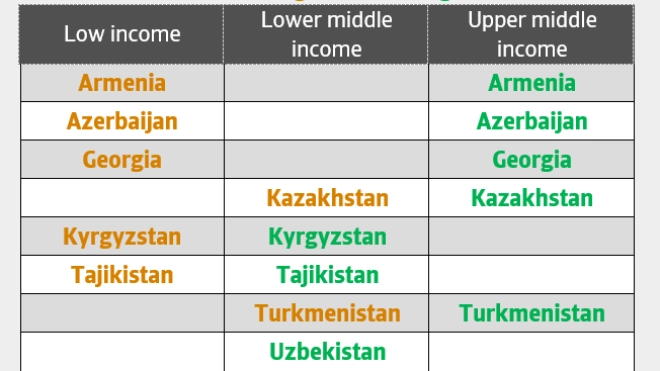

All CCA countries are now in the middle-income group (Table 1). Several countries, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, have transitioned from low-income to middle-income status in the past two decades. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan were already lower-middle-income two decades ago. In 2023, most CCA countries were in the upper-middle-income group. The exceptions are Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, which remain lower-middle-income. Uzbekistan is the only country in the CCA region that has made no promotion in income class in the past three decades. However, under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev it has implemented important reforms in recent years, liberalising its economy and improving prospects for private sector development.

For CCA countries in the upper-middle-income group, it is important to become an innovation economy, which is the second phase of structural change in the World Bank’s 3i model. Becoming an innovation economy crucially depends on human capital development and strengthening institutions. A country can develop human capital by investing in a skilled workforce and adopting economic ideas from abroad. Primary and secondary education enrolment rates in most of the CCA region compare favourably with those of developing countries with similar income levels and often match what many advanced economies can offer. At the tertiary level, however, CCA countries perform much worse. The gap has widened over the last decade, primarily due to outdated curricula, insufficient investment in educational infrastructure, and a mismatch between education and labour market needs.

Economic and political institutions also play a key role in defining a country’s long-term growth potential. Research finds a positive correlation between income per capita and democratisation, with the exception of oil-exporting countries. Additionally, market reforms can promote democratisation by fostering economic growth and reducing the power of entrenched elites. Strong economic institutions, characterized by high openness to trade and a strong rule of law, are another essential factor for achieving high-income status.

|

Box 1: The World Bank 3i framework

Central to the World Bank’s recommendations is a ‘3i’ strategy, which involves two key transitions across three phases of economic development:

Investment (1i): For low-income countries, the focus is on policies that increase investment to build the necessary infrastructure and capital base.

Investment + Infusion (2i): As countries reach lower-middle-income status, they need to adopt and spread modern technologies and successful business practices from abroad across their economies.

Investment + Infusion + Innovation (3i): Upper-middle-income countries should complement investment and infusion with innovation. This involves pushing the technological frontier by developing new products and processes, fostering economic freedom, social mobility, and political contestability.

The first transition, from 1i to 2i, usually occurs in rapidly growing lower-middle-income countries. Policymakers in these countries emphasize importing modern technologies and business models from more advanced economies and diffusing this knowledge at scale in their domestic economy. Countries that are relatively open to economic ideas from abroad and have instituted strong secondary education and vocational training programs at home tend to perform better than those that have not.

The second transition, from 2i to 3i, occurs mainly in successful upper-middle-income economies that are running out of technologies to learn and adopt. This transition involves a deliberate shift from imitating and adapting technologies used in advanced economies to becoming able to change the leading global technologies. Tapping into global knowledge and a country’s institutional infrastructure play a key role in the transition from upper-middle to high-income. |

The CCA region went through a period of rapid reforms in the 1990s, including price liberalisation, small-scale privatisation and the opening-up of trade and foreign exchange markets. But the pace of reforms slowed by the end of the 1990s, including in areas such as governance, enterprise reform and competition policy.

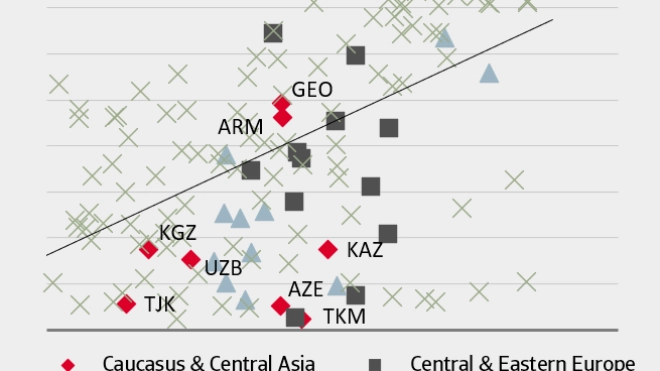

Figure 3 shows the average of four key economic indicators from the Worldwide Governance Indicators: rule of law, control of corruption, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality.

Institutional standards remain substantially below those of, for example, Central and Eastern Europe. Moreover, the institutional quality remains below that of countries with similar income levels, with the exception of Georgia.

This pattern is also evident in the relationship between democratisation and income levels. Except for Georgia and Armenia, CCA countries score much lower on the democratisation index compared to countries with similar income levels (figure 4). This gap in governance matters, as it hinders investment and prevents the efficient allocation of resources within the economy. Similarly, a lack of democratisation can hinder market reforms and thereby limit income growth. Reforms that strengthen institutions could help the CCA region to transition to high-income status.

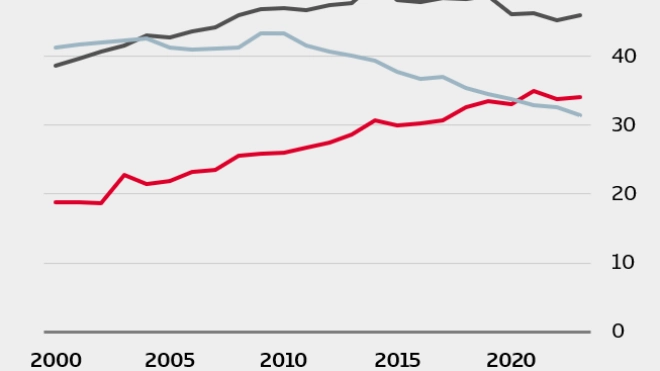

The deficiencies that still exist in the educational infrastructure and lacking institutional quality hinder growth in the CCA region and make it more difficult for CCA countries to achieve high-income status. A reflection of slowing GDP growth is that capital accumulation is lagging. Between 1995 and 2015, the capital-to-GDP ratio in the CCA region declined, from 5.3 in 1995 to 2.9 in 2015. Since 2010, investments have picked up and the investment-to-GDP ratio moved to comparable levels to that of Central and Eastern Europe. Still, the capital-to-GDP ratio in the CCA region (3.0) remains lower than in other emerging market regions such as MENA (4.2) and Central and Eastern Europe (4.7) (figure 5).

Investment plays a crucial role in explaining past episodes of growth outperformance and successful transitions of middle-income countries to high-income status. Capital accumulation alone, however, is not sufficient. In fact, the growth of middle-income countries depends on both capital accumulation and technical change. Looking at technical change, the CCA region has made substantial progress in catching up from their disadvantaged position. Productivity levels across all CCA countries now match those of nations with similar per capita income levels, a notable improvement from their lagging status in 1995.

The CCA region has also partially closed its technology gap with the United States, which is often seen as the technological frontier. This frontier symbolises the growth leader, the country with the most advanced combination of economic production, innovation, and workforce. The TFP level of the CCA region has improved from 30% of the US level in 1995 to 59% in 2019. However, the pace of technological catch-up has slowed in the past decade and the TFP level remains significantly below that of the US and Advanced Europe.

CCA countries are not making sufficient progress in either capital accumulation or TFP growth to achieve high-income status within the next decade. To address this, it is crucial to strengthen political and economic institutions and improve tertiary education. These measures can significantly enhance the investment climate and foster the development of human capital, which in turn can indirectly promote TFP growth.

Conclusion

Despite experiencing rapid growth since the early 1990s, countries in the CCA region have all remained in the middle-income bracket. In fact, the income gap with the technology leader, the US, has widened in recent decades. Growth in middle-income countries hinges on both capital accumulation and technical change, making their growth challenge twice as complex compared to low-income countries, which focus mainly on accumulation, or high-income countries, which rely largely on technical change.

For the majority of CCA countries that are in the upper-middle-income group, the challenge is to complement investment and infusion with innovation. This involves developing industrial structures and technical competencies to add value and advance the global technology frontier. Investing in human capital by cultivating a skilled workforce and adopting economic ideas from abroad is crucial. While CCA countries score well on the enrolment rates in secondary education, they fall short in the quantity and quality of tertiary education.

Strong political and economic institutions are also important factors in stimulating innovation. Countries with weaker institutions are more likely to fall into the middle-income trap. Significant institutional reforms occurred in the CCA region during the 1990s and 2000s, but the pace of reform has slowed in the past decade. As a result, institutional standards in the region remain substantially behind those in Central and Eastern Europe.

In the current situation, countries in the CCA region face a genuine risk of remaining in the middle-income trap, and more is needed to make the step to high-income status.

- After becoming independent from the Soviet Union, the countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia (CCA) underwent a turbulent transition to market economies, with varying degrees of success. The 1990s were marked by strong reform efforts, leading to high economic growth, supported by technological advancements.

- However, since the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, productivity growth has slowed considerably, impeding economic progress. As a result, while CCA countries continue to narrow the income gap with advanced economies, none have yet achieved high-income status.

- To reach this milestone, CCA countries need to boost productivity once again, which would require renewed reform efforts and substantial investment in human capital.