Optimism surged when a Government of National Unity (GNU) was formed in the summer of 2024. For the first time since 1994, the African National Congress (ANC) lost its majority in parliament and entered a coalition with the Democratic Alliance (DA). Initially, investor confidence improved, as the GNU was seen as reform-oriented, a business-friendly alliance capable of reviving the economy and restoring political stability. One year on, the outlook is more complex.

Economic progress has been uneven, the coalition appears fragile, and public confidence is beginning to fade. Tensions between the two largest coalition parties, ANC and DA, have intensified, creating political uncertainty and threatening a swift implementation of key reforms. External pressures have compounded these challenges. The return of Trump in the White House has strained US-South Africa relations. The substantial import tariffs on South Africa and the potential loss of preferential trade through the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) are expected to hit the economy. Especially the automotive sector and agriculture are vulnerable.

While facing these headwinds, the GNU needs to focus on addressing the substantial domestic challenges that have long hindered economic growth. The GNU faces a critical test: can it overcome internal divisions and deliver the reforms needed to bring growth to a higher path?

Subdued economic growth for years

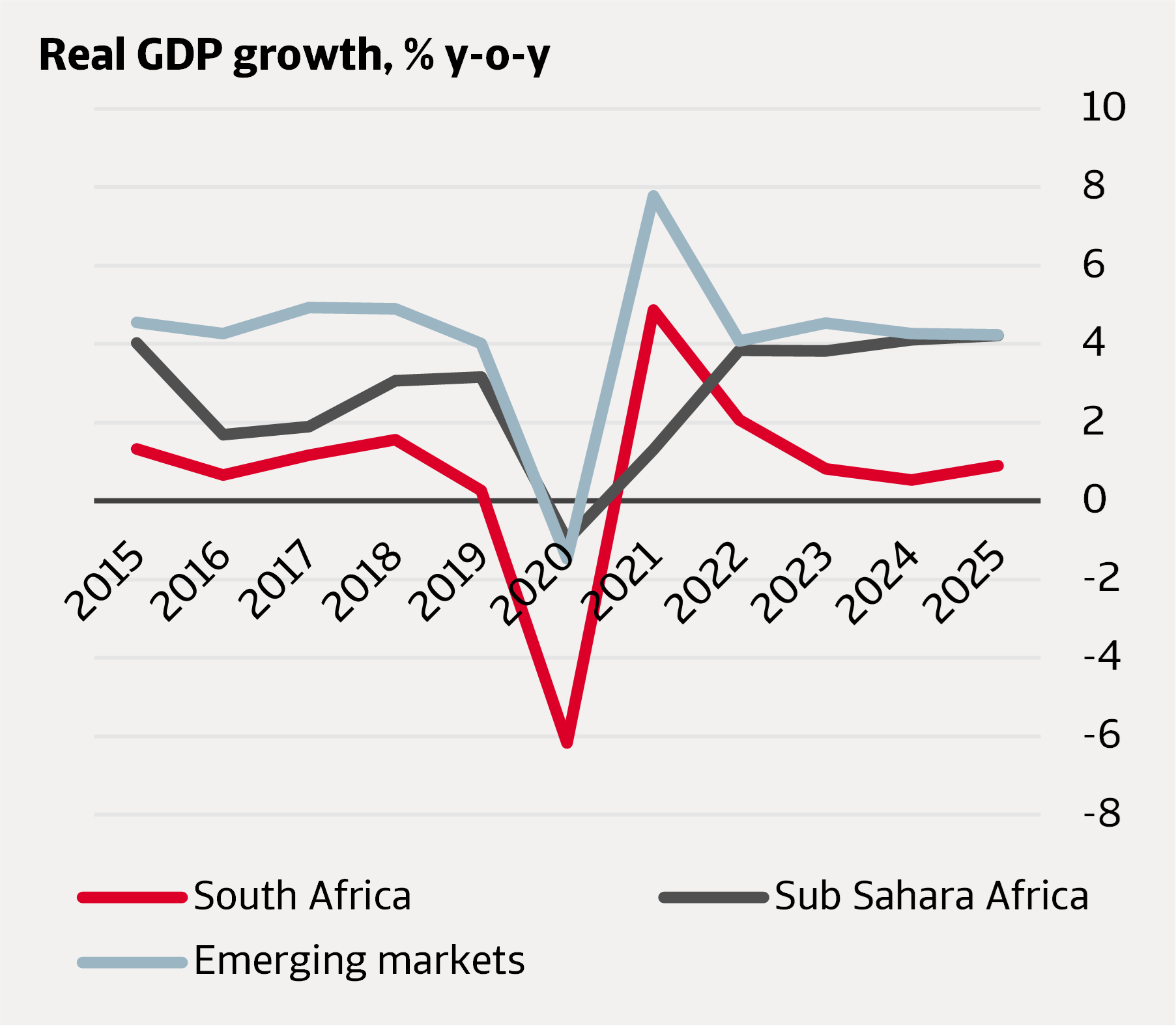

South Africa has long been one of the growth laggards in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Over the past decade, with an average economic growth of only 0.7% per year, South Africa’s growth has been extremely moderate. As seen in figure 1, it has been well below the regional and emerging markets averages. This year growth is expected to be only slightly higher. Being Africa’s largest economy, South Africa continues to struggle addressing its deep-rooted challenges, including persistently high unemployment, especially among the youth, and one of the highest inequality rates in the world.

Figure 1 South African growth lags SSA and EMEs

Source: Oxford Economics

Several diverging shocks and challenges, both domestic and external, were responsible for the subdued economic growth in previous years. These include the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020; the July 2021 social unrest; and the floods in April 2022. While these shocks have played a role, the most pressing constraints on growth are structural and domestic in nature.

Electricity woes; the Eskom burden

South Africa’s economic performance is heavily constrained by deficient infrastructure, largely due to years of mismanagement and corruption within state owned enterprises (SOEs) responsible for its development and maintenance. Chronic underinvestment and neglect have led to the poor state of infrastructure we see today.

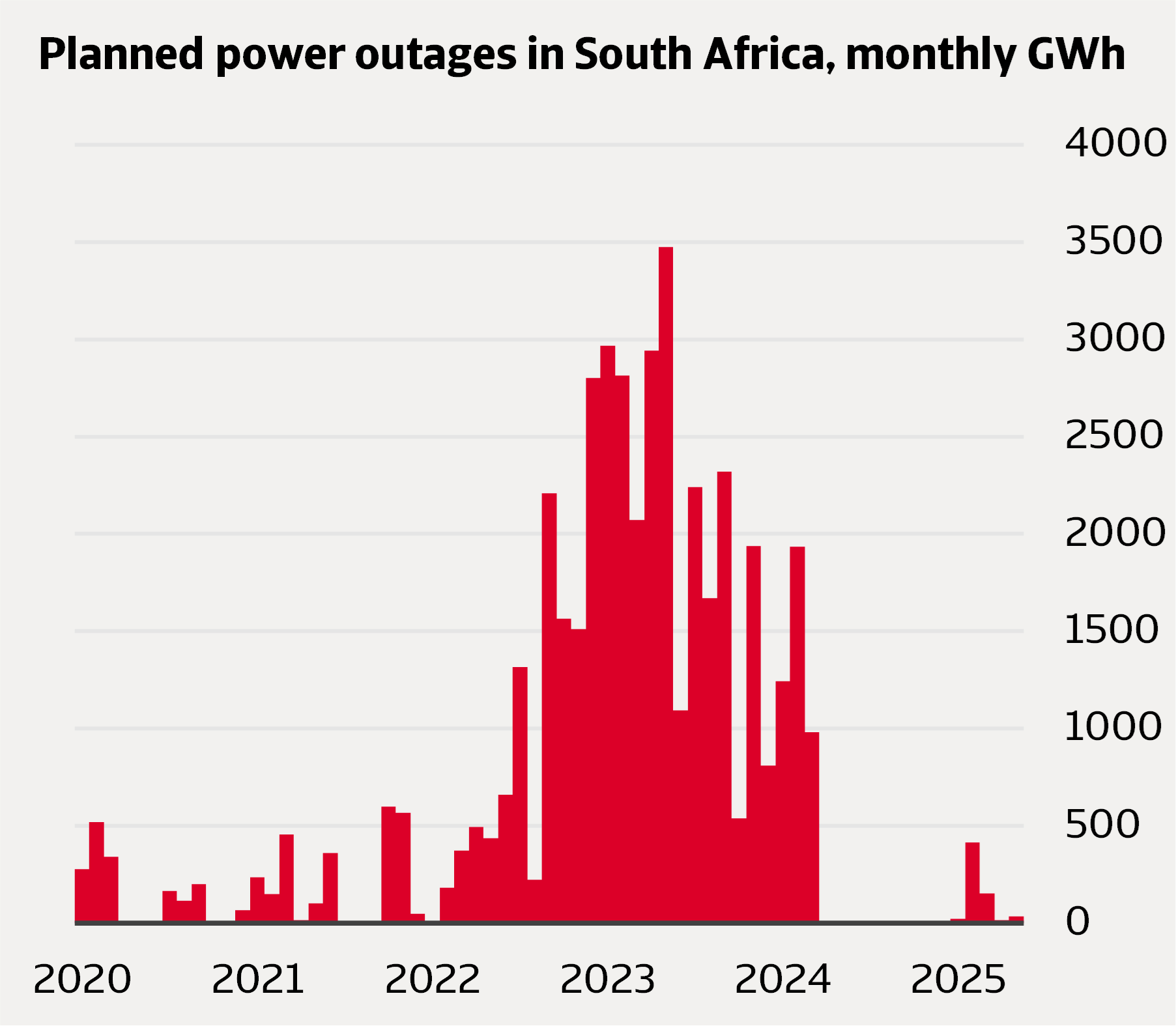

A striking example is the issue of load shedding. These are planned power outages implemented to prevent a total collapse of the electricity grid. The outages, which intentionally disconnect consumers from the grid, have a severe impact on the economy. Businesses have to halt their operations or use (more expensive) alternatives to generate electricity. In 2023, South Africa experienced the worst load shedding on record, with the OECD estimating a 1.5% reduction in economic growth as a result.

Figure 2 2023 showed the worst load-shedding

Source: Reserve Bank of South Africa

Since March 2024, the frequency of load shedding has dropped. Eskom, a SOE and the main provider of electricity, was able to bring several generation units back online after long-term maintenance. In addition, the private sector invested heavily in alternative energy sources, easing the pressure on the national grid. Despite these improvements, the electricity supply remains fragile. Load shedding returned briefly in early 2025, highlighting ongoing vulnerabilities.

Eskom, which generates 90% of the national electricity, is going through a major restructuring to address its significant financial and operational challenges. Years of poor governance and falling sales have eroded its financial health, prompting the government to provide substantial support. At the end of the 2024 financial year Eskom’s debt stood at approximately 85% of its total assets, around 8% of GDP . To support Eskom, the government introduced the Eskom Debt Relief Act in June 2023 which covered around ZAR 254 billion (5.5% GDP) of Eskom’s debt until 2026. In 2025, several amendments were made to this Relief Act. The main changes were an increase in the budgeted funds for 2025 and 2026, and a new budget allocation for financial year 2028/2029. In addition, the entire allocation for 2025 and 2026 is now structured as a loan, which can be converted into equity if Eskom meets certain conditions. Due to these amendments the government reduced its exposure and saved approximately ZAR 20 billion on the original amount, putting less pressure on the national budget. The Relief Act also imposes a moratorium on new borrowing, requiring National Treasury approval for any new debt or government guarantees.

In addition, Eskom is working to improve governance and reduce fraud. The Zondo Commission, established in 2018 to investigate allegations of state capture under the presidency of Jacob Zuma, exposed substantial governance failures, including criminal networks and political involvement, and resulted in management changes.

Thanks to the support program, and higher tariffs, Eskom’s financial and operational performance has improved. It even recorded its first profit in 8 years in financial year 2024/2025. Nevertheless, several challenges remain. Key risk for Eskom’s financial stability remains the vulnerable financial state of municipalities. They are responsible for 40% of the electricity distribution, mainly serving households and small businesses. Arrears owed by municipalities – now around 15% of Eskom’s total debt – have risen sharply. They struggle with infrastructure maintenance, theft and vandalism. Many are unable to deliver reliable electricity.

South Africa’s infrastructure challenges extend beyond electricity. The country faces widespread logistic failures in rail, ports, roads, and water systems, all of which further constrain economic growth.

Beyond electricity: transport failures

A crucial part of South Africa’s economic infrastructure is its freight rail network, operated by Transnet Freight Rail (TFR), a division of SOE Transnet. Also, Transnet is facing major operational and financial challenges, with the government providing substantial support as well.

Several rail networks connect the mining regions to various ports, facilitating the export of key commodities like coal and iron ore. For instance, one of the main corridors is the so-called North Corridor to the port of Richard Bay on the east coast. It transports around 40% of total freight rail volumes, predominantly coal . Problems in the North Corridor had a significant impact on coal exports. TFR has consistently fallen short of its coal corridor capacity target. In 2024, the target was 75 million tons, but actual volumes fell short by about 25 million tons.

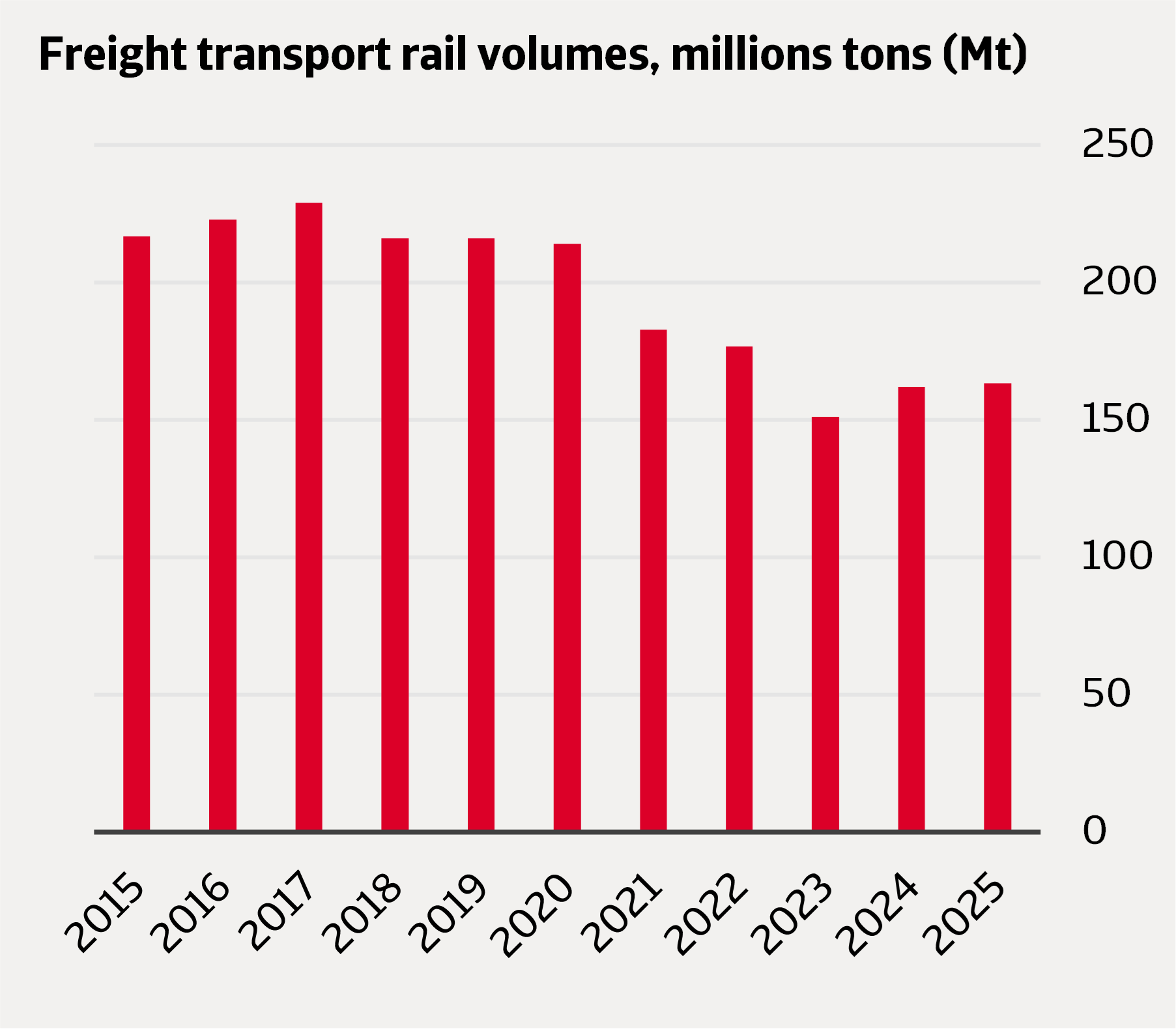

Over the years, the performance of the freight rail network has deteriorated sharply (figure 3). By 2023, the freight rail volumes were down one-third from their 2017 peak, reaching the lowest levels in years. This decline is not only due to underinvestment but also to worsening security conditions, like cable theft and vandalism.

Figure 3 Freight rail volume dropped

Source: Statistics South Africa

These bottlenecks in the freight network have reduced export and fiscal revenues, preventing many commodity producers to produce at full capacity and missing out on the price surges in coal and iron ore after the Covid19 pandemic and Ukraine’s war.

Due to the rail constraints, many exporters have turned to the road, which has caused congestion at the Port of Richards Bay and placed enormous pressure on the road network. Overall, port infrastructure suffers from operational issues and equipment failures, leading to congestion and delays. These issues not only hinder exports but also imports by affecting manufacturers that depend on imported inputs.

Logistics failures at this scale disrupt supply chains, erode investor confidence, and increase business costs. While recent improvements, especially in electricity, are encouraging, logistics infrastructure continues to pose significant constraint on growth. The government has initiated structural reforms focused on infrastructure and, despite limited fiscal room, plans to invest further in the coming years.

Although the government acknowledges the urgent need to support SOEs, it remains hesitant to privatise key entities like Eskom and Transnet. In 2024, the government adopted the Freight Logistics Roadmap, to address pressing operational challenges and increase private-sector participation. The roadmap seeks to open the network to third-party access and improve efficiency. Its overall success is however limited and uneven. The implementation of public-private partnerships has been slow and, for instance, port efficiency is still lagging global standards. Faster reform implementation and strong private sector engagement are necessary to make the roadmap successful.

Investment needs and constraints

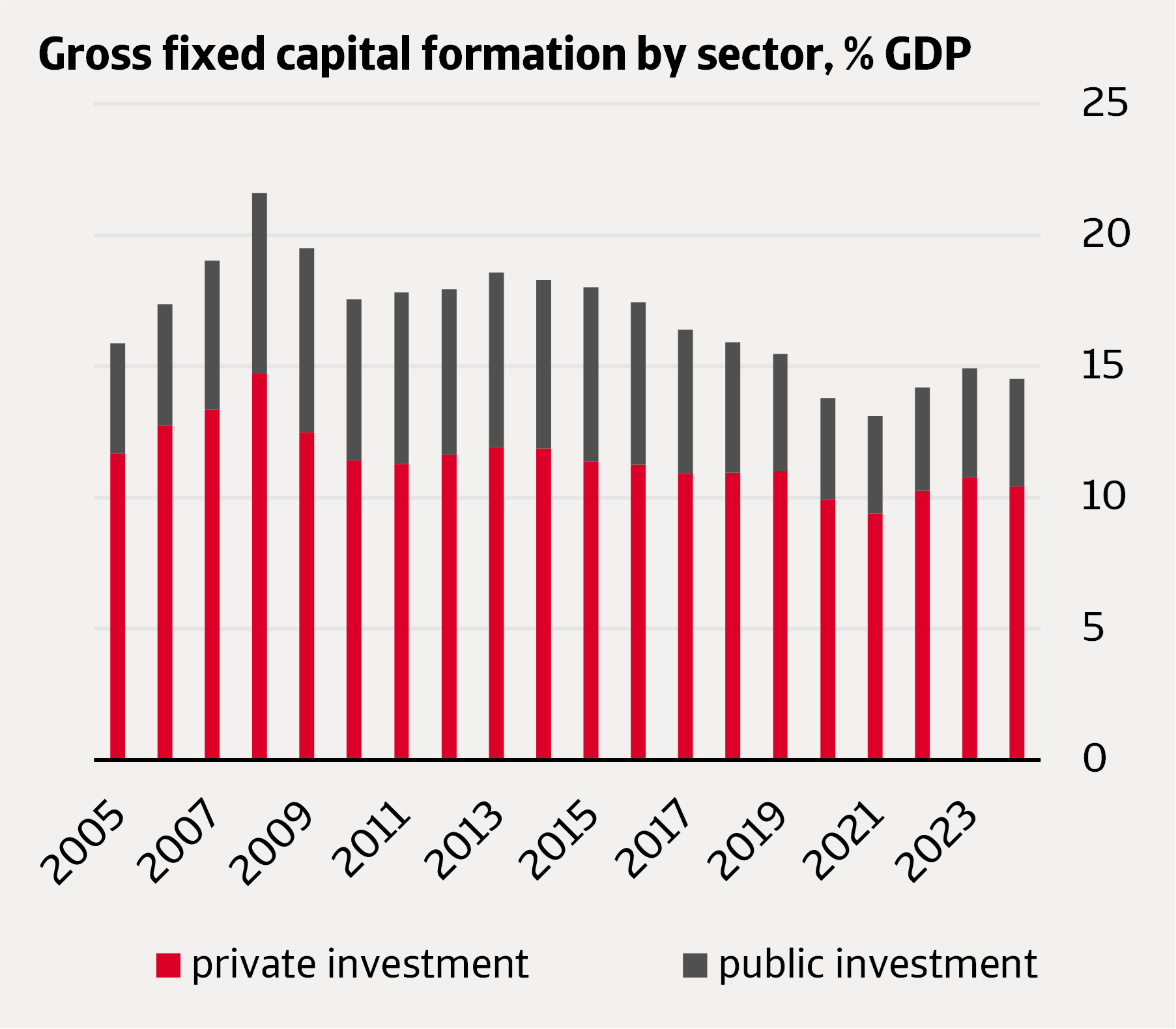

Capital investment in South Africa has been low for years. In 2024, investments were only 14.5% of GDP, insufficient to accelerate the growth needed.

Figure 4 Investments fail to pick up

Source: Statistics South Africa

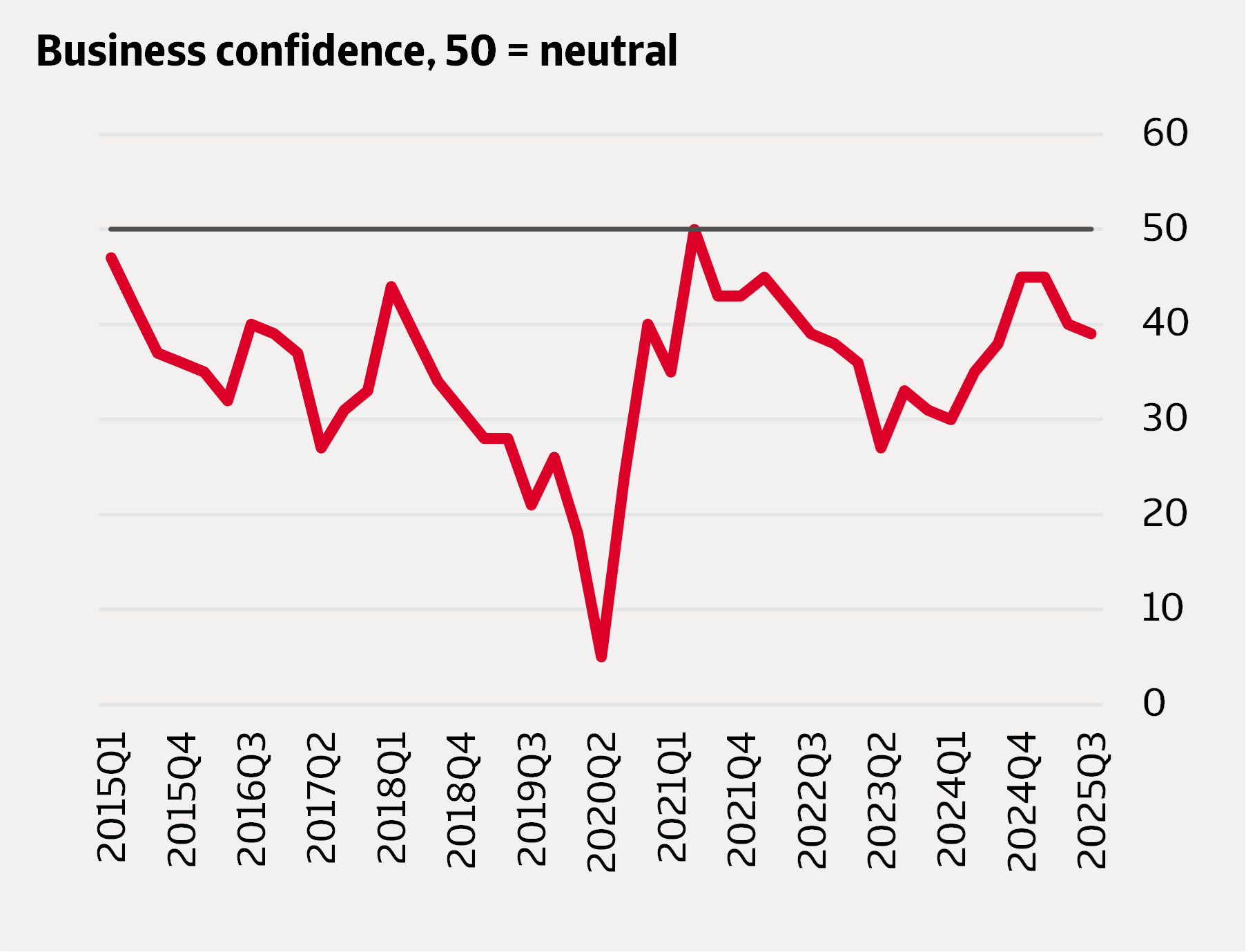

Substantial investment is undeniably required-, but from whom? The government’s fiscal space is limited, making private investment crucial. However, the structural infrastructure constraints of above, rising borrowing costs, political uncertainty and inconsistent policies have discouraged private investors over the past decade. Frequent policy shifts, unclear regulations, and slow implementation have eroded confidence. As seen in figure 5, business confidence has been below 50 for a decade.

Figure 5 Political and policy uncertainty keep business confidence low

Source: Bureau for Economic Research

To reverse this trend, consistent policy and political stability are necessary. In this context, the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) has sparked optimism, as reflected in the above graph, with rising business confidence due to its perceived market friendly stance. However, confidence declined again in the beginning of this year due to increasing tensions within the GNU and following the return of Trump in the White House, creating uncertainty with respect to the tariff levies on South African exports to the US.

GNU formation sparks optimism

In the May 2024 elections, the African National Congress (ANC) lost its parliamentary majority for the first time and could no longer govern alone. After ruling South Africa since 1994 the ANC saw a steady decline in popularity, driven by weak economic growth, poor public service delivery, and corruption scandals.

This led to the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU), a coalition of 10 political parties, with the ANC and Democratic Alliance (DA) as the largest parties. The formation of the GNU was initially seen as a positive shift, as it has a broader representation and diversity of voices, after decades of single party rule. The inclusion of the pro-business party DA also contributed to a perception of the GNU as market friendly. A government that will improve governance and introduce the necessary reforms to tackle the structural issues that constrain economic growth for years now.

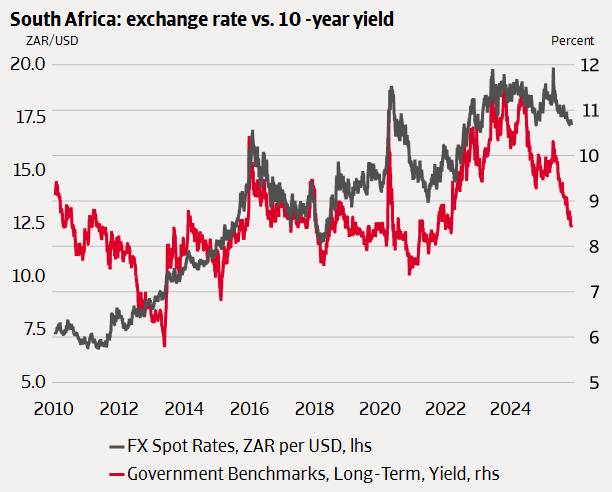

Following the GNU’s formation, not only did domestic business confidence receive an uptick, but also financial market sentiment. The rand appreciated, borrowing costs declined, and interest from non-residents to buy local-currency government bonds increased.

Figure 6 Market sentiment initially improves

Source: Statistics South Africa

The GNU has committed to addressing South Africa’s most pressing challenges and fostering inclusive economic growth. Over the coming years it will focus on three strategic priorities.

- First, it aims to stimulate inclusive growth and job creation through economic reforms and substantial infrastructure investments. This includes restructuring SOE’s, enabling greater private sector participation, and leveraging SA strengths in green manufacturing, renewable energy, and natural resources.

- Second, the GNU seeks to reduce poverty and alleviate the high cost of living by expanding social support and investing in education, healthcare and housing.

- Third, it is dedicated to building a capable, ethical, and developmental government with emphasis on improving governance, tackling corruption, and enhancing public safety.

These priorities are closely aligned with Operation Vulendlela (OV) launched by the ANC in October 2020 to accelerate structural reforms. Phase I of OV is considered successful, with most proposed reforms either completed or on track. Key achievements include opening the electricity sector to private investment and allowing private participation in ports and rail.

Despite this progress, economic growth has remained subdued. According to the government, a key constraint is the deteriorating performance of local governments. Municipalities have a central role in policy implementation and the delivery of some basic services. Next to electricity distribution, other basic services include for instance water supply, municipal roads and sanitation. Many municipalities suffer from weak governance, funding shortfalls, and an inability to deliver basic services. Another identified growth constraint is spatial inequality – rooted in apartheid-era planning – that continues to hinder access to economic opportunity for many poor households. Addressing these constraints and building on the reforms already taken in phase I are central to phase II of Operation Vulendlela. This phase prioritises the transformation of the electricity sector, improvement of the logistics system, securing reliable water supply, strengthening local government capacity, tackling spatial inequality, and accelerating digital transformation.

...but is challenged by internal divisions

One year into the GNU, initial optimism is fading as tensions between ANC and DA intensify. There have been several disagreements between the two, with DA voting against some proposals.

Earlier this year, three versions of the 2025 budget were necessary because the DA voted against the proposed VAT increase in the first version. With the support of other smaller parties, the GNU successfully passed its 2025 budget. It was not the first time the DA opposed legislation; contentious bills like the Land Expropriation Act and the Basic Education Laws Amendment Act were passed despite their opposition.

In June 2025, tensions escalated when President Ramaphosa removed the DA deputy minister of Trade, Industry and Competition following his unauthorized visit to the United States. The DA responded by withdrawing from the National Dialogue. Accusations of frustrating cooperation within the GNU are being made back and forth. The DA accuses the president of making unilateral decisions without consulting coalition partners, including the signing of legislations without prior discussion. They also feel the ANC is not taking sufficient actions against corruption within its ranks . The ANC, in turn, is complaining about the DA’s actions and lack of commitment to coalition success.

Distrust has simmered since day one of the coalition. The ANC, having won only 40% of the vote, needed support from other parties to re-elect Ramaphosa. As South Africa’s constitution dictates that the National Assembly nominate a president within two weeks of the final election results, there was little time to come to an agreement between coalition parties. Initially, the coalition consisted of the ANC, DA and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), which re-elected Cyril Ramaphosa as president. It grew into a multiparty coalition when president Ramaphosa invited other parties to join the GNU. A move the DA objected. Ten parties signed the coalition’s founding document, the Statement of Intent, which stipulates that decisions are made when the two largest coalition parties reach sufficient consensus. In case of disagreements, these have to be referred to a dispute resolution mechanism, which the DA claims is not operating effectively.

It appears that the GNU was formed out of necessity to prevent the more radical Zuma’s MK party and Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) from entering the government. The ANC needed other parties to govern, and the DA saw an opportunity to influence policy. Not unimportantly, market pressure also played a role. The steadily depreciating rand and the rising borrowing costs for the government, reflect the eroding investor confidence over the past years. A coalition including the DA was seen as a change from the past.

However, the DA’s influence is limited due to the multiple parties in the GNU and by its underrepresentation in cabinet. For instance, the DA holds six minister positions (out of 32) and six deputy minister positions (out of 43). Given the ideological and policy differences between the ANC and the DA cooperation was never expected to be easy. Still, there was hope that shared goals would unite the parties to govern. Tensions between the two are likely to persist, potentially undermining reform efforts and creating political instability. Yet, it is unlikely that the DA will step out the coalition, as it now has an opportunity to govern. With local elections on the agenda in 2026, both parties have strong incentives to maintain the coalition. One year in, the GNU remains a work in progress.

Looking at the persistent tensions within the coalition, it is most likely that the government will muddle through, creating uncertainty and slowly implementing structural reforms. Hereby being cautious to implement the most ambitious reforms, which are highly needed to accelerate growth. Therefore, we expect that economic growth will remain modest in the coming years. In 2026, growth will be slightly higher at 1.1% due to the recent improvements in electricity supply and steps toward private sector involvement in logistics. In addition, growth will be supported by the expected recovery in private consumption due to the pension reform. However, the impact of US tariffs will negatively affect economic activity in the near term. Further improvements in electricity and logistics will contribute to an increase in economic growth towards 2030. Although this increase is limited as growth is expected to move around 1.8% towards 2030.

Navigating fiscal constraints

While structural reforms are essential, they must be complemented by increased public investments. However, the weak government finances constrain the GNU’s ability to significantly increase investments, deliver basic services and meet pressing social needs.

Despite these fiscal constraints, the GNU is investing approximately ZAR 1 trillion in infrastructure, with major allocations to transport, energy, water, and sanitation. While these investments are critical for long-term growth, they contribute to ongoing fiscal pressure.

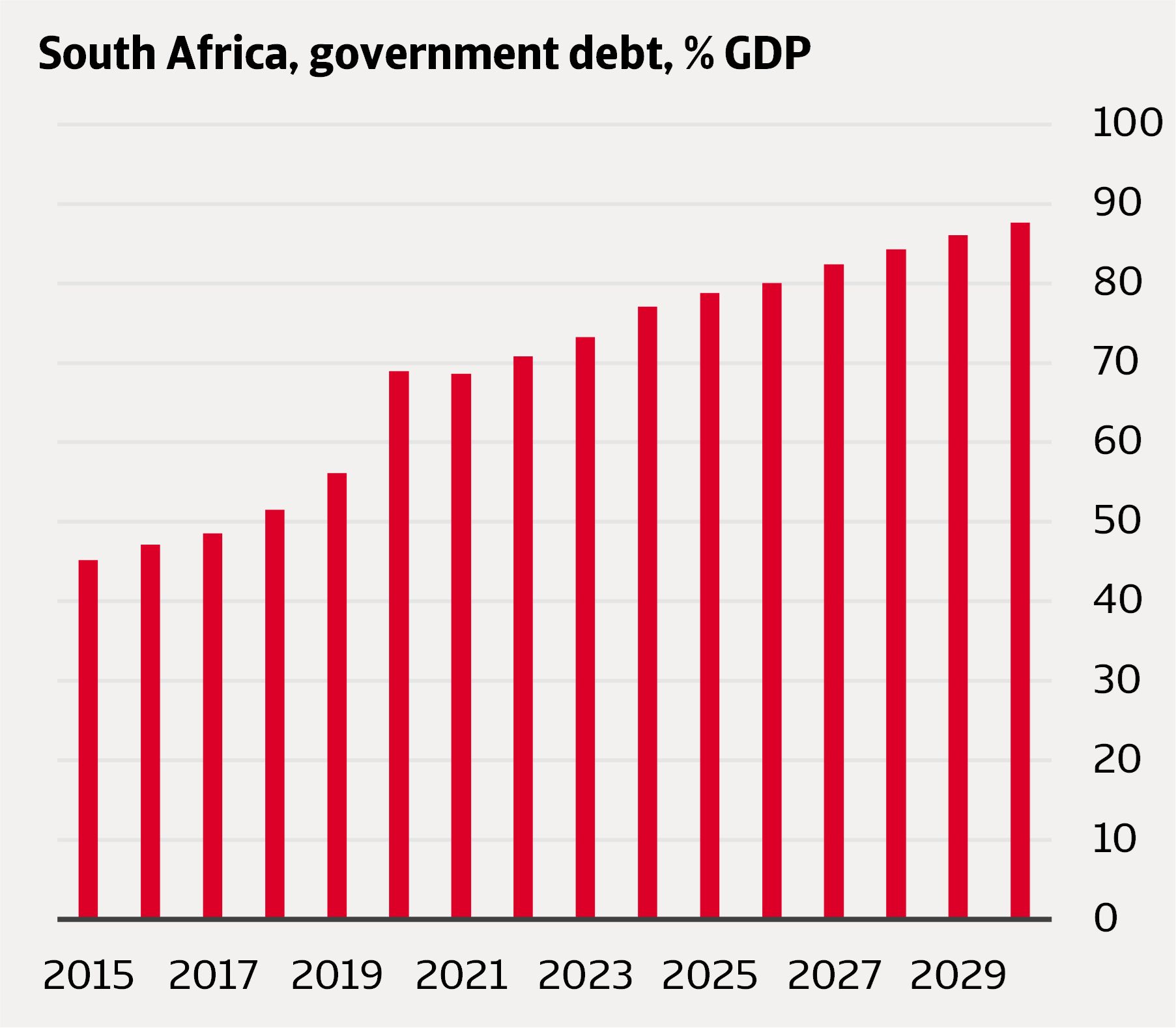

Over recent years, South Africa showed persistently high budget deficits, leading to a sharp increase in public debt. In 2024, total public debt reached 77.3% of GDP, up from 45.2% in 2015. It is expected that public debt will remain elevated. Although the GNU is committed to fiscal consolidation and maintaining debt sustainability, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to deteriorate slightly in the coming years. This is not due to rising nominal debt, but because of low economic growth.

Figure 7 Elevated debt levels

Source: Oxford Economics

Despite South Africa’s elevated public debt levels, several mitigating factors help to manage associated risks. These are the relatively long average maturity and the large share of rand-denominated debt. The average maturity of government bonds is around 11.3 years, reducing the financing risk. The share of local currency is around 90% of total public debt, reducing the exposure to currency risk. Historically, non-resident investors played a significant role in financing government debt. However, as fiscal conditions have deteriorated non-resident investors steadily lost their appetite. The share of non-resident investors in government bonds dropped from 40% in 2017 to 25% in 2024. Domestic institutions have largely filled this gap, underscoring the depth and strength of South Africa’s well-diversified local capital market.

Nevertheless, the high debt burden has led to a significant rise in debt-servicing costs, which increased from 14.3% of fiscal revenues in 2018/19 to 21% in 2024. Interest payments now exceed spending on health, education, and social development.

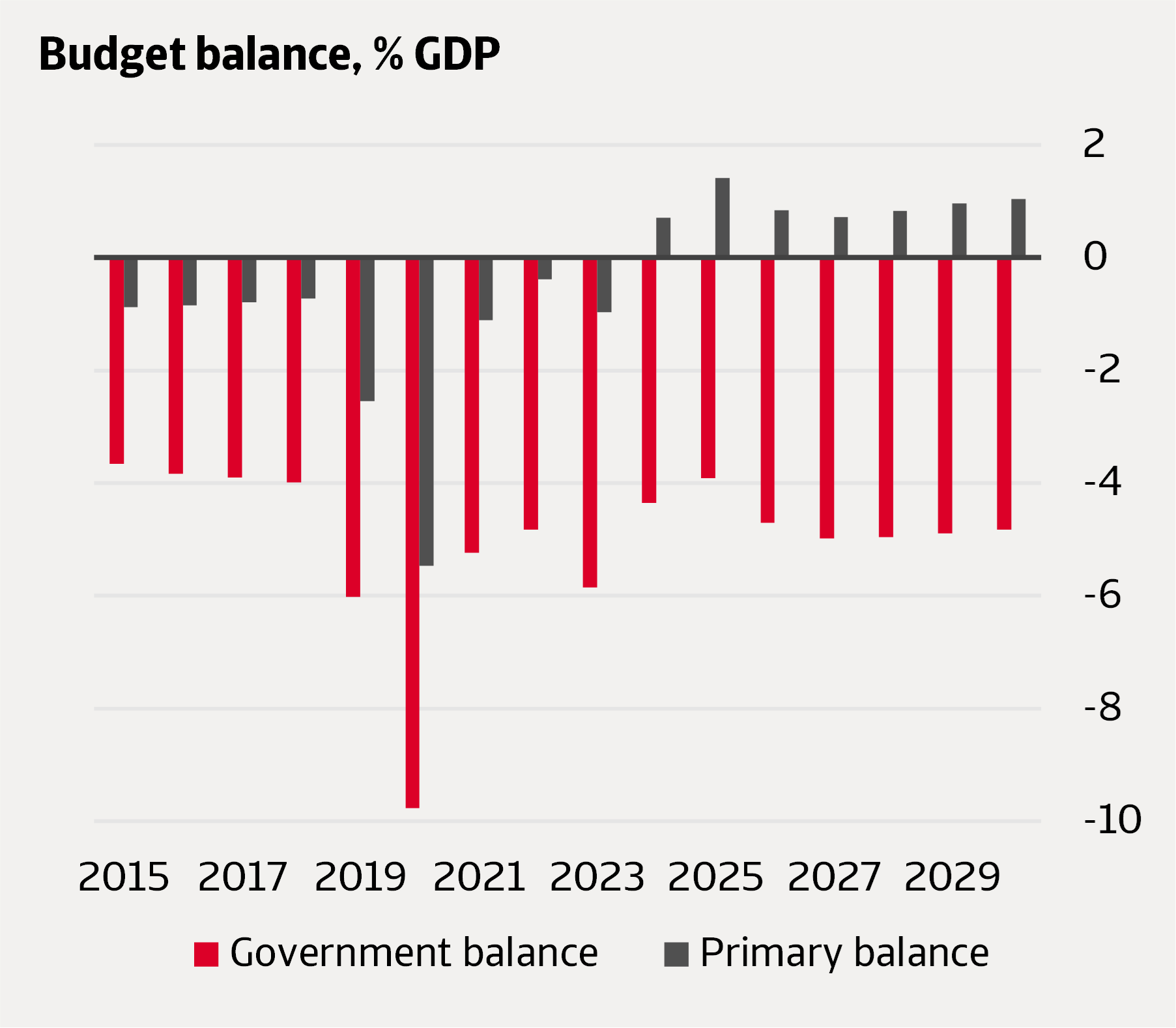

To ensure debt sustainability in the medium term, the GNU remains committed to fiscal consolidation. This commitment, however, must be balanced against pressing social and economic needs, resulting in persistent high budget deficits in the near future. The decision to abandon a planned VAT increase has further weakened the fiscal outlook.

A central pillar of fiscal discipline is the effort to increase the primary budget surplus. In fiscal year 2023/2024, South Africa recorded its first primary surplus since 2009, with further surpluses projected in the coming years. Consolidation efforts will be focused on cutting inefficient spending and increasing tax revenues. Especially limiting the public sector wage bill is one of the priorities. Currently, public wages consume around 30% of total expenditure. One of the measures to reduce this is encouraging voluntary early retirement. Next to this, the government will reduce its bailouts to SOEs.

A positive development was the transfer of ZAR 100 billion from the South African Reserve Bank’s Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account (GFRECRA) to the National Treasury in fiscal year 2023/2024. This helped reduce funding pressure. In addition, the implementation of the two-pot retirement system in September 2024 , is expected to support fiscal revenues through increased taxable withdrawals.

Despite these efforts, significant risks to the public finances remain. These include the precarious financial situation of SOEs, and the government guarantees extended to them. Persistently low economic growth and the weak financial situation of many municipalities further compound fiscal vulnerabilities.

Figure 8 High budget deficits despite primary surpluses

Source: Oxford Economics

Balancing growth and stability

South Africa stands at a critical juncture. While the Government of National Unity (GNU) has laid out promising reform strategies, the key challenge now lies in accelerating implementation. Implementation of additional structural reforms, particularly in energy, logistics and governance, are essential to further build investor confidence, unlock private sector participation, and place the economy on a higher growth trajectory.

Although economic growth is expected to improve in the coming years, it will remain insufficient to address deep-rooted issues like high unemployment and inequality. Planned reforms and public investments should ease electricity and transport constraints, supporting economic growth in the near term. However, weak public finances, persistent infrastructure failures, and the fragile situation of key SOEs (especially Eskom and Transnet) continue to undermine economic performance.

A meaningful uptick in growth requires more. Reform delivery is likely to be slow, hampered by tensions within the GNU, while current plans lack ambition in areas critical for private investment, such as business regulation and labor market flexibility. These reforms face ideological resistance within the ANC, making near-term progress unlikely.

Political stability is key to success. South Africa’s economic outlook hinges on the GNU’s ability to maintain political stability. The internal tensions and ideological differences pose risks to reform delivery. Keeping the GNU together will be essential. The GNU must navigate a delicate balance: advancing reforms while maintaining political stability within a diverse coalition and pursuing fiscal consolidation without stifling investment in critical infrastructure and social services. The success of this balancing act will determine whether South Africa can overcome its structural bottlenecks, reduce inequality, and achieve higher, inclusive economic growth.

- The mid-2024 formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU) in South Africa initially boosted investor confidence, as it was seen as business friendly and committed to much-needed reforms to accelerate growth

- For years, economic growth has been subdued, with deficient infrastructure – particularly the underperformance of key state-owned enterprises Eskom and Transnet – being a significant constraint. Persistent low economic growth, eroding investor confidence and fiscal constraints have kept investment levels low

- A swift implementation of reforms and increased investments are essential to unlock faster, more inclusive growth. To achieve this, collaboration between the coalition partners, the African National Congress and the Democratic Alliance, remains key